Paper cranes - Duke - Example AMCAS personal statement

Example AMCAS personal statement

From a young age, I was taught to value generosity and kindness. My parents emphasized both local and international philanthropy, encouraging me to volunteer everywhere from the library to the international food packing and distribution center for developing nations. While they rarely discussed their charitable activities, I saw the donation requests arrive in the mail daily: March of Dimes, the Susan G. Komen Foundation, American Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders. The list goes on, but with one theme: medicine. Whether funding medical supplies or medical research, the pattern caught my attention. I wondered why they chose these nonprofits. What so distinguished medical philanthropy and service? I had to find out.

This curiosity led me to volunteer at the local hospital, where I caught a glimpse of medicine in full color. I saw frustrated patients—in pain, desperate to go home. I saw beaming patients, welcoming new life into the world. I saw family members, nervously anticipating news of loved ones. I saw friends, waltzing down the hall with flowers and balloons. I saw all these things and I wanted to be a part of it—to make a difference, to be more than an idle observer of happiness and sadness, to tip the balance in favor of joy.

One day, I was making usual rounds through the emergency room when I met Mrs. Hall:

“Would you like another blanket and a newspaper to read, ma’am?”

“Sure, honey,” she nodded warmly.

I returned with both items and a smile.

“Be right back with your water.”

“Why do you always do this?!” She exclaimed, pushing the blanket to the floor. “I just want to go home.”

She crossed her arms and looked away. Dr. Hoverstadt, an emergency medicine physician I had shadowed many times, walked in.

“Mrs. Hall, you know you can’t go home yet. Let’s talk about your other options.”

I turned to leave but was motioned to stay as Dr. Hoverstadt explained Mrs. Hall’s choices at Palo Verde or Sonora Behavioral Health. Mrs. Hall was a bipolar patient.

“No! Anywhere but Sonora! I’m not going!”

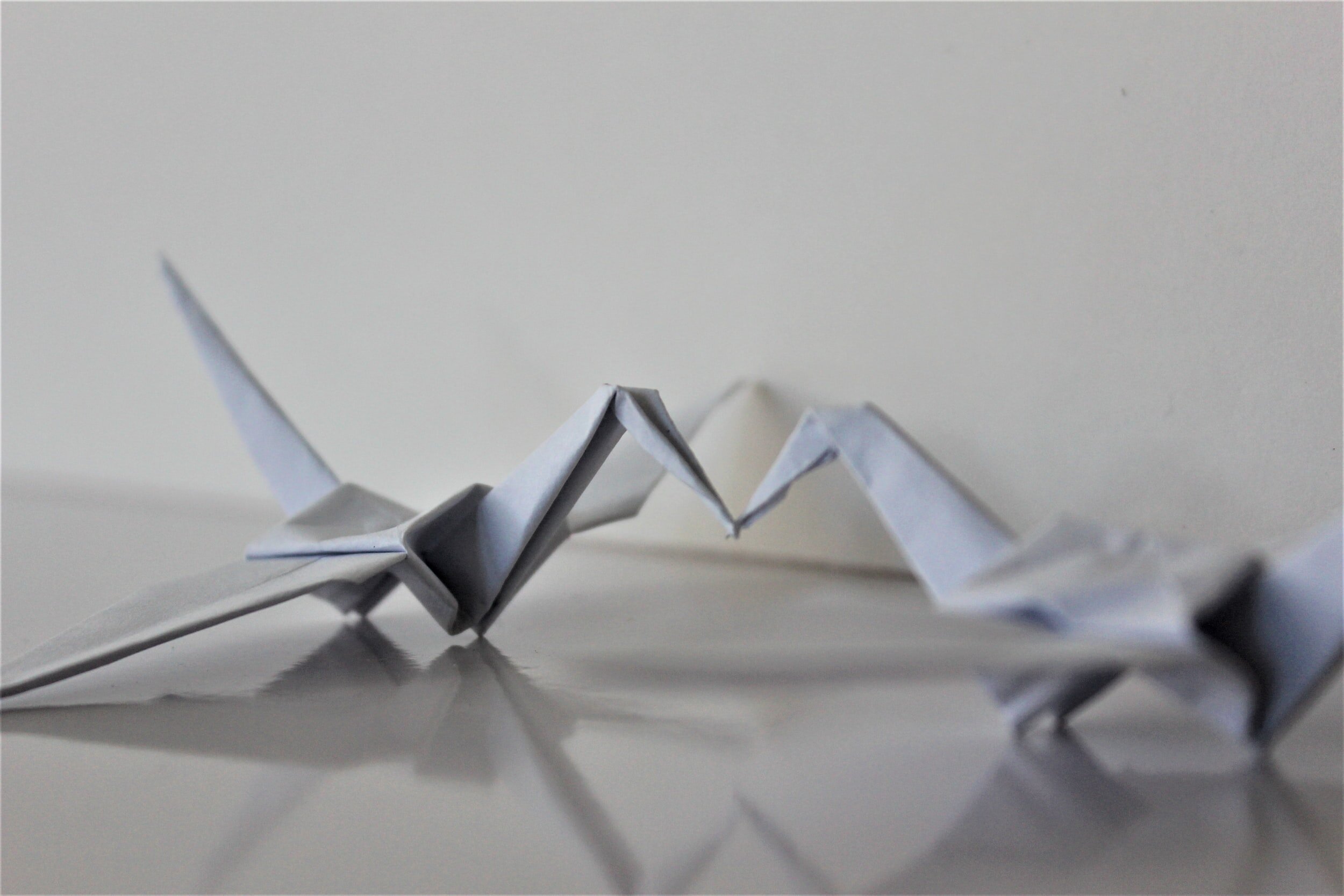

Dr. Hoverstadt calmly reasoned with her, but it seemed hopeless. I ventured to help, pulling out a post-it origami paper crane. Dr. Hoverstadt gave me a knowing nod.

“Mrs. Hall, this is for you.”

Her previously listless eyes dropped to my hands—then her face lit up.

“Darling, it’s adorable!” She exclaimed, taking the crane in her palm. “Did you make it?”

I answered yes, explaining the folkloric power of making a wish on 1000 paper cranes. I offered her one of my wishes, from having previously folded 1000s of cranes. Mrs. Hall’s eyes sparkled as she faced Dr. Hoverstadt again.

“Maybe Palo Verde?”

By most definitions of medicine—diagnostics, orders, scans, prescriptions, physical exams—my presence contributed little value. But in the holistic sense of patient care—where physicians serve as healthcare providers, I had joined Mrs. Hall’s care team.

Although that origami crane was smaller than the palm of my hand, it symbolized much more for Mrs. Hall. Maybe it renewed her hope, or reminded her of loved ones, or reinforced the thoughtful attention of her medical team. At the very least, it distracted her from care-obstructing frustration to make way for a necessary conversation with her physician. In the end, a simple gesture visibly impacted the progression of Mrs. Hall’s care.

Not only that, but Mrs. Hall’s delight—how it rapidly blossomed with just a few tender words—remained with me. It was not the first origami crane I had ever given, nor the last, but it was by far the most memorable. For me, Mrs. Hall’s beaming response served as a reminder of what I, even without medical training, could add a patient’s treatment. But I wanted to give patients more, in ways requiring my pursuit of an MD.

That night, I continued serving patients’ basic needs, but Dr. Hoverstadt also invited me to tag along for rounds and assist in identifying patients for clinical trials. By the end of the night, dozens of origami cranes had landed in the north and central pods of the emergency department. Even the trauma bay saw a few flocks fly through. Time and time again, patients’ smiles revealed the immense impact of small words and gestures, ones that seemed to powerfully shape Mrs. Hall’s world—in addition to mine.

Meeting Mrs. Hall reminded me of the value held by thoughtfulness in human interactions. While small gestures are not a novel concept, her appreciation encouraged me to more deeply view the road of medicine as one laden with opportunities to serve others—to be as generous and kind as I had been taught. “Doctoring” is concretely physiological, but also vastly abstract and emotional. The latter has motivated my participation in the medical process, and with every origami crane, the patient and I both gain (just a little) from sharing in the human experience. This component arguably matters most.

My future began here, and pursuing an MD will fuel my journey to more profoundly serve others at home and abroad. Until then, generosity and kindness will be my tools for making a difference—even if only one small crane at a time.